The blogs I will be posting will share teaching practices that have had a high-impact on teachers and their early grade literacy learners in Kenyan and Ethiopian low-resource schools. More specifically, I will focus on the critical space between teacher and student; the space where the magic happens or not. There are issues, however, that call for a lens adjustment – a wider lens for a broader perspective. This blog addresses one of those issues.

Reading comprehension, although an implicit goal of reading instruction and a widely stated goal at that, often remains stuck in the “Unsatisfactory” column on local, national and international assessments. This is deeply troubling. Far from being just one of many academic areas taught and assessed in schools, reading comprehension is the whole enchilada. Not being able to make meaning from print has a cascade effect on the life of a child. From the perspective of the young student, not being able to get what the words say is demoralizing and incentive destroying. From the point-of-view of the parents, particularly in rural areas in developing countries, when their child is not able to keep up and pass tests, it’s time to replace school with work. From the standpoint of the school establishment, students who cannot pass advancement exams, usually given in grade 5, will not have a path to higher education.

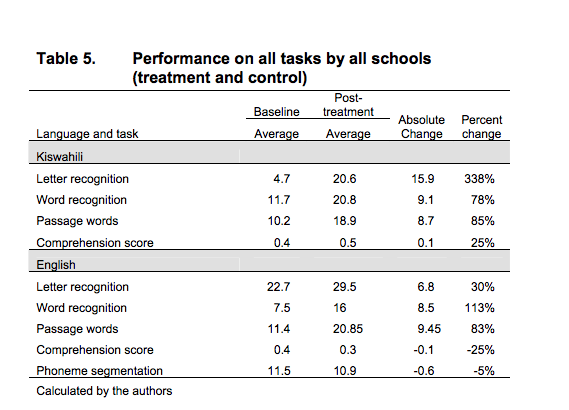

Given that succeeding to read well in school is recognized as being so vital to all segments of society and given that since the inception of All Children Reading: A Grand Challenge for Development, (2011), which led the way to focusing on early reading, we are left wondering why the epidemic of non-readers in the developing world, and to a much lesser extent in the developed world, continues to this day. How is it that: even when schools are focused on improving their students’ reading achievement; even when carefully constructed literacy programs are implemented; even when the needed resources are allocated; even when books in the students’ first language are provided; even when there is by-in from the parents and community; even when teachers are receiving professional development and coaching; we repeatedly see little more than a tick up on reading comprehension? (See Fig. 1) While not claiming to have the answers to these questions, I do want to raise considerations that fall outside the field of data gathered in well-documented studies.

|

| Figure 1. Improvements in Reading Skills in Kenya: An Experiment in Malindi District |

First a clarification: I am not equating word recognition with reading. Phonemic knowledge, decoding words by sounding them out, and recognizing words on sight are one part of the reading process – the word recognition part. I have had many students who are champions in that area. (By my count, I’ve taught reading to approximately 2,000 children.) A cohort of the word recognition champs were able to read the words on the page fluently – they read words accurately, smoothly, with good phrasing and expression. Before mediated instruction, however, they could not recall, explain, question, discuss or relate to what they read. In other words, they could not read!

So, what could help us understand the reading comprehension conundrum? I hope you will weigh in on this, but here are my thoughts on the reasons reading comprehension outcomes are so disastrous, particularly in low-resource schools:

- The age-old tradition and persistent practice of taking turns reading aloud or round-robin reading in class, understandably focuses the teachers’ attention on their students’ oral reading behaviors. And naturally enough, merit is assigned to fluent “reading”. (You don’t have to be a teacher to visualize waiting for a slow and halting reader with 20 more students cued up for their turn.) In this setting, comprehension either happens or it doesn’t.

- The programs that have been introduced over the last decade, aimed for teaching basic literacy and they assessed basic literacy. A heavy emphasis was placed on skills needed for word recognition and fluency while comprehension was given a back seat in the classroom. This was also the case for writing. Expressing ideas in writing enhances and reinforces students’ word recognition and builds their understanding of how written language works (e.g., sentence structure, grammar and vocabulary).

- When phonics, which provides clues for unlocking words, becomes the end-game, comprehension becomes an after-thought, if at all. Children who are taught to meet every word on a page as an exercise in sounding out each letter, need a lot of reteaching before they start to think about what the words are saying.

- While teaching phonics is not complex, teaching comprehension is complex. It requires more than a manual. It requires thinking on your feet. Comprehension, beyond the literal level (locating or recalling answers to who, what, when and where questions) requires discussion and discussion takes time. Leading a discussion in very large classes is daunting unless the teacher is aware of management options.

- Students’ responses to text, when reading for higher-level understanding (original thinking), will be diverse; each reader will use their own experiences and level of language to make meaning. Teachers have to be comfortable with more than one answer to a question and they need to value the information the children’s answers provide about their understanding.

- Fixing poor comprehension requires explicit instruction. Teacher-education courses seldom or never prepare students for providing explicit strategy lessons. (i.e., “I see you are having difficulty coming up with answers that are not stated in the book. I will show you how I do that.”)

- The most daunting challenge to students’ reading comprehension is a school’s inability to provide its students with a teacher or a text that sounds like the language in the home. There have been great strides made in producing early reading materials in multiple languages and matching beginning readers’ first language with their language of instruction. However, sound instruction will remain a prerequisite to reading and writing proficiency.

- Teacher education, teacher education, teacher education. In many places it is not long enough, deep enough or rigorous enough to prepare teachers for the complex work of teaching reading comprehension.

In my coming blogs, I’ll double back and elaborate on practices that impact the issues I’ve touched on here. What are your thoughts, comments, suggestions and questions on the reading comprehension conundrum? I look forward to reading them in this space.

No comments:

Post a Comment